Carcassonne was originally released by Hans im Gluck in 2000. It won the SdJ that year, and since has become a phenomenon. There are now 4 large Carcassonne supplements, 4 small Carassonne supplements, and 5 variant games. Within our Eurogame community, only The Settlers of Catan has been more successful in sheer bulk of releases.

Carcassonne was originally released by Hans im Gluck in 2000. It won the SdJ that year, and since has become a phenomenon. There are now 4 large Carcassonne supplements, 4 small Carassonne supplements, and 5 variant games. Within our Eurogame community, only The Settlers of Catan has been more successful in sheer bulk of releases.This week I'm beginning a series that will analyze that phenomenon--talking about how Carcassonne works and also examining how the game system has evolved over the last six years. This first installment will examine the mechanics of the original game, while in future articles I'll be talking about how the game has evolved through a series of expansions and new games.

Before we get started, if you're now familiar with the game and its supplements, you may want to look at my reviews of the same. I've fallen down on the more recent Carcassonne supplements, because I don't feel like they fit the vision of the original game (which I'll talk about in the next few articles), and I haven't bought Leo Colovini's Discovery because I don't agree with its manner of distribution, but everything else is there.

Original Carcassonne Reviews: Carcassonne w/River (B+), Inns & Cathedrals (B), Traders & Builders (A-), King & Scout (B+), The River II (C)

Carcassonne Variant Reviews: Carcassonne: Hunters and Gatherers (A), The Ark of the Covenant (A), Carcassonne: The Castle (A-), Carcassonne: The City (A)

Not Reviewed: The Count of Carcassonne, The Cathars, The Princess & The Dragon, The Tower, Carcassonne: The Discovery

Analyzing the Gameplay

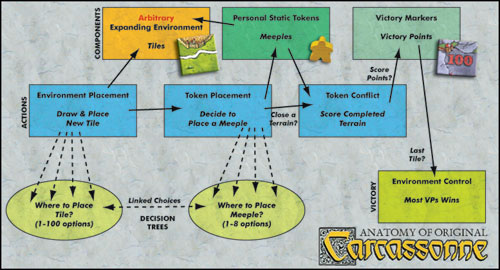

Last week I provided a broad overview of terminology for analyzing gameplay. Though I'm sure I'll use it again in the future, the immediate purpose was to provide a lexicon for this article. Broadly, Carcassonne's gameplay is very simple, but I'm going to break it down part-by-part.

Components. Each player has a small set of static personal tokens which he'll use to mark ownership of terrains in the game, but which don't move once they hit the board.

The board, meanwhile, is a classic example of an evolving environment that's constructed turn-by-turn. Each of the tiles used to create this board is accessed via an arbitrary draw, which we'll get back to when we cover Luck.

Activity. The overall activity of Carcassonne is split, linearly, among three parts: play a tile; play a token (meeple); and score completed terrains. As with most games, these activities are ultimately defined by component interaction.

The first activity is best defined as environment placement: you're creating the board through your tile draws.

The placement of the meeples, meanwhile is token placement. You're moving a token on-board, and will never be able to scoot it around the environment.

Finally the scoring portion of the activity centers on token conflict. Or, to use a more common term, it's majority control. It took me a long time to see it, but Carcassonne actually falls into the same category of games as El Grande or (perhaps more clearly) Entdecker. It's about getting the most personal tokens into an environmental area to control and thus score it. Carcassonne looks a bit different because you're building out the environment as you go, and because getting multiple tokens into a terrain is actually a trick rather than a standard mechanic, but nonetheless it follows a lot of the same conventions as the broadly understood majority-control category of gameplay.

Decisions. Last week I spoke of decision constraints and the need to keep options small; Carcassonne sort of tries to follow the "rule of 7" that I suggest, which means it tries to constrain any individual decision to just 7 options, to prevent a player from becoming totally paralyzed. But, it doesn't do so perfectly, especially not for inexperienced players.

Technically when a player draws and places a tile this is largely unconstrained. The tile could go in any legal space in the board, which is usually a couple of places at the start of the game, but could be a hundred (or more) different places by mid-game. I find this a serious problem for first-time players, who don't know how to quickly analyze the best board positions, and thus take agonizingly long amounts of time to decide where their tile goes.

A more experienced player usually quickly constrains a choice to 7 or less options. First, he looks at his current on-board positions (which, as it happens, maxes at 7 tokens), and sees if the newly drawn tile may be useful to: (1) close out a position; (2) expand a position; or (3) block others from getting into his position. Alternatively the player sees if he can use the tile to create any new on-board positions, and again this is usually constrained by a couple of "best choices" at any time. Finally if and only if he can't expand, he can't close, and he can't create, then the player may use a tile solely to block other players. Each of these main categories of options is pretty individual, and a good player will usually assess which is best based on the tile, on his current positions, and on his current token supply--but a new player can't.

Technically where a player positions his token on a tile is almost always constrained to seven or less options (excepting, perhaps, some road crossroads which could give the options of four road placements and four field placements, for a grand total of 8). However in actuality there isn't good separation between the placement of a tile and a placement of a token. The one so directly affects the other that they might as well be one decision. Thus a good player figures out his token placement as part of his 7 or less options that he quickly assesses when he looks at a tile, while an inexperienced player just sees it as a multiplier to his tile-placement decision, thus meaning that all told he probably sees several hundred choices. For me this has proven a very real failing of the game when playing with a certain type of relatively serious gamer who has some problems with Analysis Paralysis and hasn't played much Carcassonne. I literally can't play with them because games take hours.

Luck. The main luck in Carcassonne is arbitrariness, which comes about through the draw of the tiles. Some people see a ton of luck in the game, but I think it's phenomenally well controlled, and that's because of the multiple tokens. You can easily set yourself up in a situation so that most draws will benefit you: one type of tile drawn might expand your city, one might build out your road, and one might keep people out of your field. The original version of the game was a bit more "lucky" than later versions, solely because roads were always less valuable than cities, and thus you could do poorly if you only drew them. This has been corrected in most later versions, and through the expansions; I'll talk about this balancing act in the next article in this series.

The remaining luckiness tends to revolve around getting a very specific tile that you need. However, I think this "luckiness" actually results from poor gameplaying. If you're waiting for one specific tile, and there aren't many of it, then you shouldn't have let yourself get into that situation (or else you should congratulate your opponent who put you there).

There is also chaos in Carcassonne, and this centers around the landscape of the game changing between your turns. As you'd expect, the chaos factor gets bigger the more players you have. In a 5-player game you can have set yourself up with a perfect, well-defended city, then have one opponent place a tile which makes you vulnerable, and have another take advantage of that, all before it can back around to you. The arbitrariness of the tile draw can also multiply the chaos, since it can sometimes be several turns before you can respond to something.

Because of the chaos factor, I think the ideal player number for Carcassonne is 3. Two really doesn't work, for reasons I'll discuss when I talk about the Carcassonne variants (in part five of this series) while with 4-6 the chaos keeps cranking up.

Victory. Finally, looking at victory conditions, we realize that the token conflict activity translates into environment control victory. The exact formulas for those environmental control valuations are a bit varied, but the basic idea is obvious: the more environment you controlled during the game, the better you'll do.

The following chart shows these various elements of Carcassonne's game design in a more graphical format. Note that the different elements are color-coordinated. Arrows represent interrelations between the parts of the game and dashed lines represent decisions.

You can click on the diagram to see a larger version.

What I found particularly notable about the chart as I put it together is how simple Carcassonne really is. There's just a couple of components and just a few decision points, but the result is a very rich, replayable game.

Carcassonne Strategy

I don't really intend this to be a full strategy article, but I think it's worth looking at a few points of Carcassonne strategy to show how they illuminate the gameplay.

I already mentioned one of the most crucial bits of Carcassonne strategy, which is that you need to play a multivaried game. You have multiple tokens and you should use them to insure that every tile draw is a good one. If you've got good fields, good cities, and good roads, then tile draws will always help you out.

Much strategy comes from how precisely the tiles are laid. You have to make sure that you place tiles so that it's easy to complete your terrains, and hard to get boxed in. In addition you have to try and place your tiles so that it's hard for opponents to get into your terrains. You could probably write an entire article just on these intricacies.

A lot of the strategy of Carcassonne comes through a balance between cooperation and competition, which are elements that I'm going to talk about more two articles from now.

Cooperation means that you should try and share terrains with some of your opponents, particularly those opponents who are behind you in scoring. You'll both get points and you'll jointly earn more points than you could have individually. Inexperienced players can think that sharing a terrain with an opponent is bad, but this just isn't the case in a 3+ player game--unless the player getting into your terrain is ahead of you in scoring.

Competition means that you should try and harm your opponents, particularly those who are ahead of you in score, and particularly when you can do so without costing yourself actions. Placing a tile in such a way that it makes it harder for an opponent to close a terrain is almost always better than placing that tile somewhere out of the way, provided that your own token placement opportunities are similar in both opportunities. An experienced player will know a couple of the rarer tile types (for example "road, field, city, field", or if you prefer "a road running into a city" of which there is only one tile in what I call "classic Carcassonne") and may purposefully block a player by creating the need for that very rare tile. I'll get quite specific about tile distribution in the next article in this series.

Conclusion

Carcassonne is a very simple game system that nonetheless provides a lot of depth. However, that simplicity has also begun to change through many supplements. In my next three articles in this series I'm going to talk about Carcassonne's expansions; as we'll see, the gameplay has changed and evolved over the last five years, and if you're playing a game with all the expansions, you are playing a very different game from the original gameplay experience.

However, I don't want my portion of Gone Gaming to become the all-Carcassonne-all-the-time channel, so I'll be taking a break next week to discuss a different topic. But I'll see you in 14 to discuss game balance and tile distribution, with an emphasis on the "good" Carcassonne expansions.

3 comments:

Most excellent article!

I was actually going to write up a little "old and new classics" series focusing on the major mechanic of area control, and I ran into the same thoughts about Carcassonne. The fact that both tile placement and token placement (which you point out are very linked in your article) both contribute to area control is actually a little bit unusual in area control/majority games. Usually the landscape isn't dynamic. Also, it's arguable that the development of environment is a little more important than token placement---you block and extend through tile placement. This also masks the "traditional" view of area control.

Another area control game that also has the dynamic environment development characteristics of Carcassonne is Trias. However, traditional area control is a bit stronger in Trias, if only because you have multiple dinosaurs roaming around in an area, rather than the Carcassonne "one per land feature" mechanic. But Trias' continental drift is controlled by players (with some luck in the draw of the cards) and is very important to keeping your majority control alive in particular areas, or to even to shift it around.

Excellent analysis of Carcassonne and it's strategies. The simplification (via chart) made so much sense. Just thinking logically, based on your common-sense approach, gave me a fifty point advantage in my last game. One special friend (300 miles away) and I keep a game going all of the time. We do not share strategies but do congratulate each other on great moves without going into detail. This is enough competition for us and makes us eager to return.

There can be an element of chivalry to this wonderful game. Hard-fought battles with a worthy opponent while trusting in an honorable relationship to that opponent is possible in few games. Maybe that is why Carcassonne is so alluring, especially for two women players. I felt you, of all commentators, would understand this. I've learned a lot about chilavry throughout history from my husband. Men may be more aggressive, but they can still show admirable respect for an opponent. This is a lost art that Carcassonne can bring back in fantasy.

Interesting article but this lkine jumped out at me:

"Finally if and only if he can't expand, he can't close, and he can't create, then the player may use a tile solely to block other players."

This is incorrect. Often the first priority is stopping the other player. Hurting the other guy is helping you so whether you build on your projects or mess up his, it is all good.

Post a Comment