When it comes right down to it, playing games has very little to do with playing games.

Consider the difference between eating and eating.

When one person sits down to eat, he needs to fill his belly and enjoy the taste while doing so. He doesn't eat when he is not hungry (unless it's cake) and he doesn't think much about the food development process, only whether he likes the results.

When another person sits down to eat, it is quite a different story. The food is examined and assessed. The wine is held up to the light and swirled. The dishes of the meal are deconstructed into parts, while the experience is evaluated as a whole.

Two different objectives for essentially the same activity, yet the perspective of the participants is so vastly different. Not only does one possess a different sensibility and subjective taste from the other, their conscious purposes are also different.

Whether or not they enjoy the meal depends only partly on any objective quality of the meal. It also depends on what they want out of a meal.

When Joe and Mary Average sit down to play a game, not only do they have different tastes than that of the prototypical gamer, they also have different reasons for playing. The Averages are playing to be entertained, to connect with their children, to pass the time, and so on. The gamer is playing to strategize, to evaluate, and to milk out an experience.

With such different possible reasons for playing, you might as well say that we are not even doing the same activity. Playing a game is not playing a game, any more than drinking to get drunk is like drinking to learn about wine. They only share some common physical props and methods.

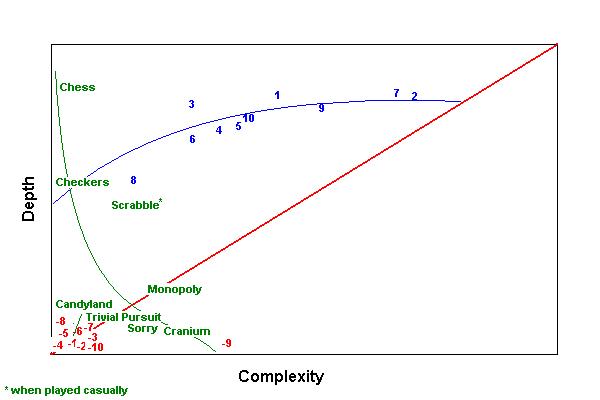

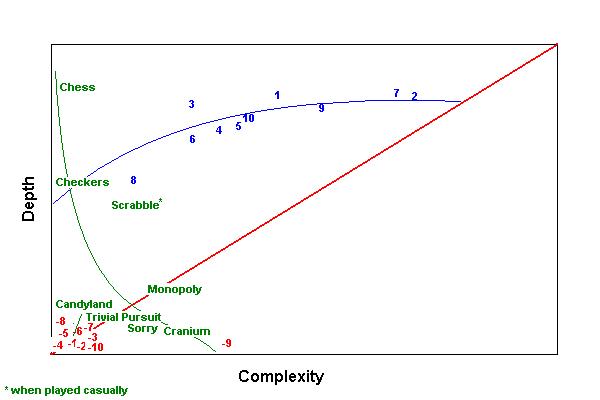

If they were the same activity, but gamers simply liked "better" games, you would expect a chart comparing game types and tracking game likes and dislikes to follow a roughly linear curve, with gamers enjoying games at one end of the curve and the Averages enjoying games from the other end or middle of the curve. But consider the following:

The blue numbers are the top games on BGG, the red numbers the bottom 10, and the green names are a sampling of the top games enjoyed by the Averages.

You can see here that it is not a case of enjoying games at different parts of the curve. There are two distinct enjoyment curves that have nothing to do with each other. You would never even know that we were looking at the same activity.

What we need here are two different names for two different activities.

The Averages can continue to "play games". Maybe we "participate in ludographic recreational activities". Would you care to study ludography with me? Yes, please, but only one glass; I have to drive home.

Instead of "game groups", how about "ludography groups", subtitled "the study of board game cultures and game interaction"? You and I know that these are still fun, but when those Averages tell us that our games are boring, we can just say that academic studies generally appear to be so to those not steeped in the academic environment. And when they ask us why we don't like to play Barney's Chutes and Ladders, we can truthfully say that "we don't play games".

We separate two people who cannot convince each other why they enjoy entirely different activities. As usual for most arguments, the problem is our disagreement on more fundamental issues: not whether this or that game is any good, but what constitutes "good" for playing games.

Having separated the two activities, we can now make better distinctions. For "playing games", "good" means what the Averages want. For "ludography", "good" means what gamers want.

Another conflict solved.

Now on to more important matters. Rewriting the song "My Humps", because it annoys me.

The Blue Eyed Sesames sing "My Hephelumps"Oscar:(What you gon' do with all that junk?

All that junk inside your can?)

I'ma get, get, get, get, real mad,

Get real mad, yes that's my plan.

My junk, my junk, my junk, my junk, my junk,

My junk, my junk, my junk, my lovely little dump. (Check it out)

Mr Snufflepagus:I drive these muppets crazy,

Cause I am big and lazy,

They talk about me nicely,

They never really see me.

Larry, Gina Jefferson,

Elmo, Mr. Robinson,

Ernie, Bert be starin'

But my vision they ain't sharin'

I only got Big "Bad" Bird,

He tries to speak a few words

And tell 'em 'bout my livin'

They say 'no', an' they keep givin'

Out like I ain't out here

It's really dip that all year

That they all keep on dissin'

But it ain't all my business.

My Snuff, my Snuff, my Snuff, my Snuff

My Snufflepagus

My Snuff, my Snuff, my Snuff,

My Snufflepagus,

(He's got me spinnin'.)

(Oh) Spinnin' round and lookin' for me, but you ain't gonna see me.

(He's got me spinnin'.)

(Oh) Spinnin' round and lookin' for me, but you ain't gonna see me.

Oscar:(What you gon' do with all that junk?

All that junk inside your can?)

I'ma get, get, get, get, real mad,

Get real mad, yes that's my plan.

(What you gon' do with all those cookies?

All those cookies on your plate?)

I'm a make, make, make, make a mess

Make a mess, make a - Wait!

Cookie Monster:OH COOKIES! OH COOKIES! COOKIES! COOKIES!

I'm gonna eat you up, my yummy cookie lumps. (Oh yum yum yum!)

Elmo:Elmo met a girl down by the sidewalk.

She said to Elmo "Hey, yeah let's go.

I could be your mommy, and you could be baby

Let's spend time together

And we'll be best friends forever

I'll give you milk and cookies

You can dip your cookies in my m ... hey, wait!"

Cookie Monster:COOKIES! COOKIES! (yum yum yum, weck it wout)

Big "Bad" Bird:They say I'm just a big bird

With birdie brains - it's absurd.

They always try to 'teach' me

Always saying words to me

Like "Can I say 'number 5'"?

Can I say 'number 5', man?

Now tell me what you're jivin'

Of course I can be fiving

Do I look like I just sprouted wings?

I talk to them real slowly

Cause they don't seem to get me

I got more brains in my feathers

Then they all got all together.

Oscar:

My dump, my dump, my dump, my dump,

My dump, my dump, my dump, my dump, my dump, my dump.

I love my little dump (dump)

I love my little dump (dump)

I'm lovin' all my junk (junk)

In the back and in the front (front)

Mrs Piggy:

My lovely Kerrrrmyyyy....

Kermit:

She got me hoppin'

Mrs. Piggy:

(Oh) I'm gonna get you froggy, froggy, you can't run from me, from me

Kermit:

She got me hoppin' (gulp)

Mrs Piggy:

(Oh) I'm gonna get you froggy, froggy, you can't run from me, from me

Ernie:

What you gon' do with all that junk?

All that junk inside that trunk, Bert?

Bert:

I'ma gonna, gonna, throw it out,

In the garbage pail, Ernie.

Ernie:

What you gon' throw it out in,

Throw, throw it out in, Bert?

Bert:

Uh, I'm gonna use the garbage pail

The garbage pail, just like I said, ... Ernie.

Ernie:

This garbage pail's got a hole in it,

Hole in it, it's a piece of junk, Bert.

Bert:

Whatever! You can jus' just throw it out

Throw it out, with all the junk, Ernie.

Ernie:

Yeah, but how should I throw it, throw it out,

Throw it out, yeah, how, Bert?

Bert:

Argh! Just put it there with all that junk,

Inside that trunk. All right, Ernie?

Ernie:

Yeah, but what you gon' do with all that junk?

All that junk inside that trunk, Bert?

Bert:

Aiiiieeeeyyyeeeee!

This song was brought to you by

(Oh) The number five, five, a beautiful number (Ah ha haaa! *crash*)

This song was brought to you by

(Oh) The letter "b", the letter "b", whis'prin' words of wisdom, letter "b".

The end.

Yehuda

Grover:

OK, OK, here is Grover, here is Grover. Grover is ready for his solo. OK.

What? Where did everybody go? Oh, I am a sad, late Grover monster.